Boubacar Traoré

The vital connection between Mali and the Mississippi.

Site artist : www.boubacartraore.com

Facebook – Youtube

About

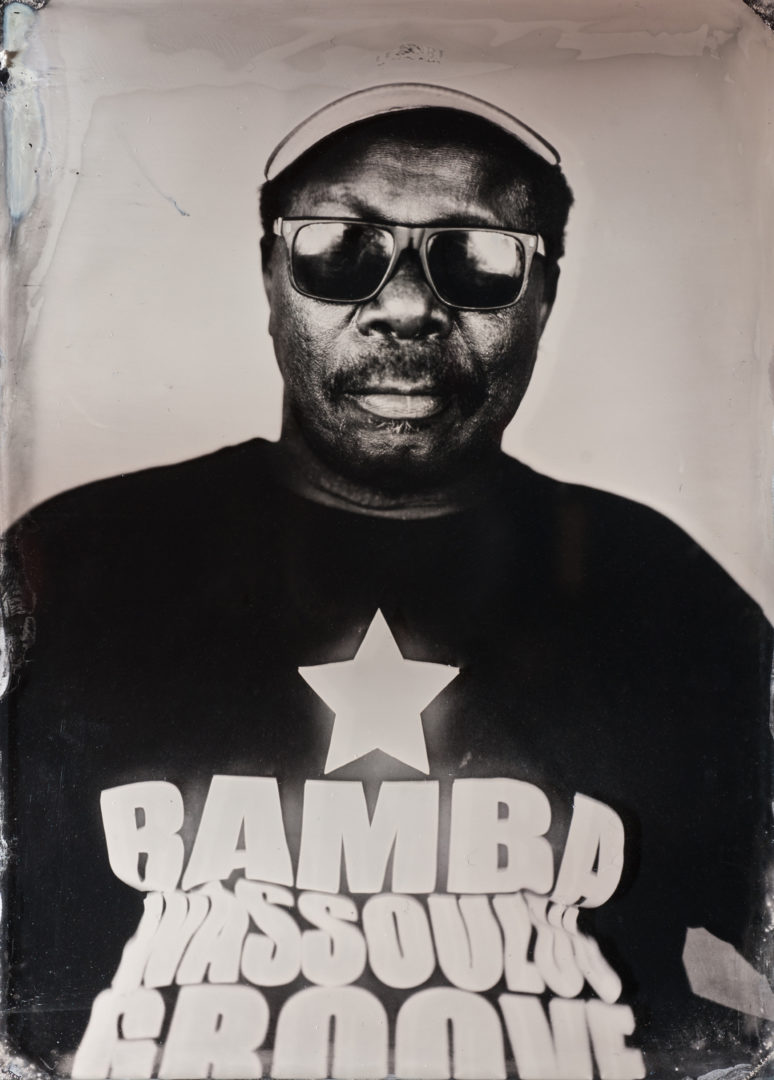

Boubacar Traoré carries within him all the beauty of African blues. A diamond among the jewels of Mandingo music, he shines with the dark glow of exceptional purity. Only the voice of “Kar Kar” (a footballing nickname meaning “The Dribbler” given him by his friends, who also love the beautiful game) can blend Niger and Mississippi river alluvia with such moving authenticity. His unique, inimitable, self-taught guitar technique owes a great deal to his kora influences, but its shades and phrasing also suggest the great black bluesmen of the deep South: Blind Willie McTell, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters and others.

Back in the 60s when the euphoria of African independence reigned, the 20-year-old Boubacar Traoré was Mali’s Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley. He was the first to play Mandingo-based music on electric guitar, long before his junior, Ali Farka Touré. In those days, Malians would wake to the sound of Boubacar’s poignant voice and saturated riffs. Hits including “Mali Twist” (Children of independent Mali, we must stand on our feet / Let all the young people return to their homeland / We must build the country together) and “Kayeba” provided dance music for a generation who were enjoying freedom for the first time. But then the celebrations and lyrical illusions ended. On the 19th November 1968, a bitter wind blew across Mali when Modibo Keita’s socialist government was overthrown by a military coup. Kar Kar and his songs were exiled from the airwaves. Returning penniless to Kayes, his hometown in the Kassonké region (to the northeast of Bamako near the Senegalese border), Boubacar became a farm worker, opened a shop with his elder brother – the one who had introduced him to the guitar and given him his first one – and worked to feed his family.

He was rediscovered in 1987 when reporters from Malian national television visited Kayes. “Kar, you have to come to Bamako. You’ve never been seen on television since it began. Everyone should realise you’re not dead, you’re alive…” It was a renaissance for the artist. “People were amazed to see me. Most of them had only heard me on the radio,” he said at the time. Yet fate was to put a stop to Kar Kar’s musical rebirth. Pierrette, his beautiful mixed-race wife, his muse, his love, died bringing their last child into the world. Despairing and distraught, Kar Kar became a shadow of himself. It was then that he decided to look for work in Paris, where he joined the community of Malian migrant workers and shared their harsh life. “I was a building worker for two years,” is his only comment on this personal experience, but one of his songs says it all: “You can be a king at home, but when you’re a migrant, you’re a nobody.” The legacy of his time in the Barbès immigrant quarter of Paris and the hostel in Montreuil where he sometimes performed is the flat cap the tall Malian wears today.

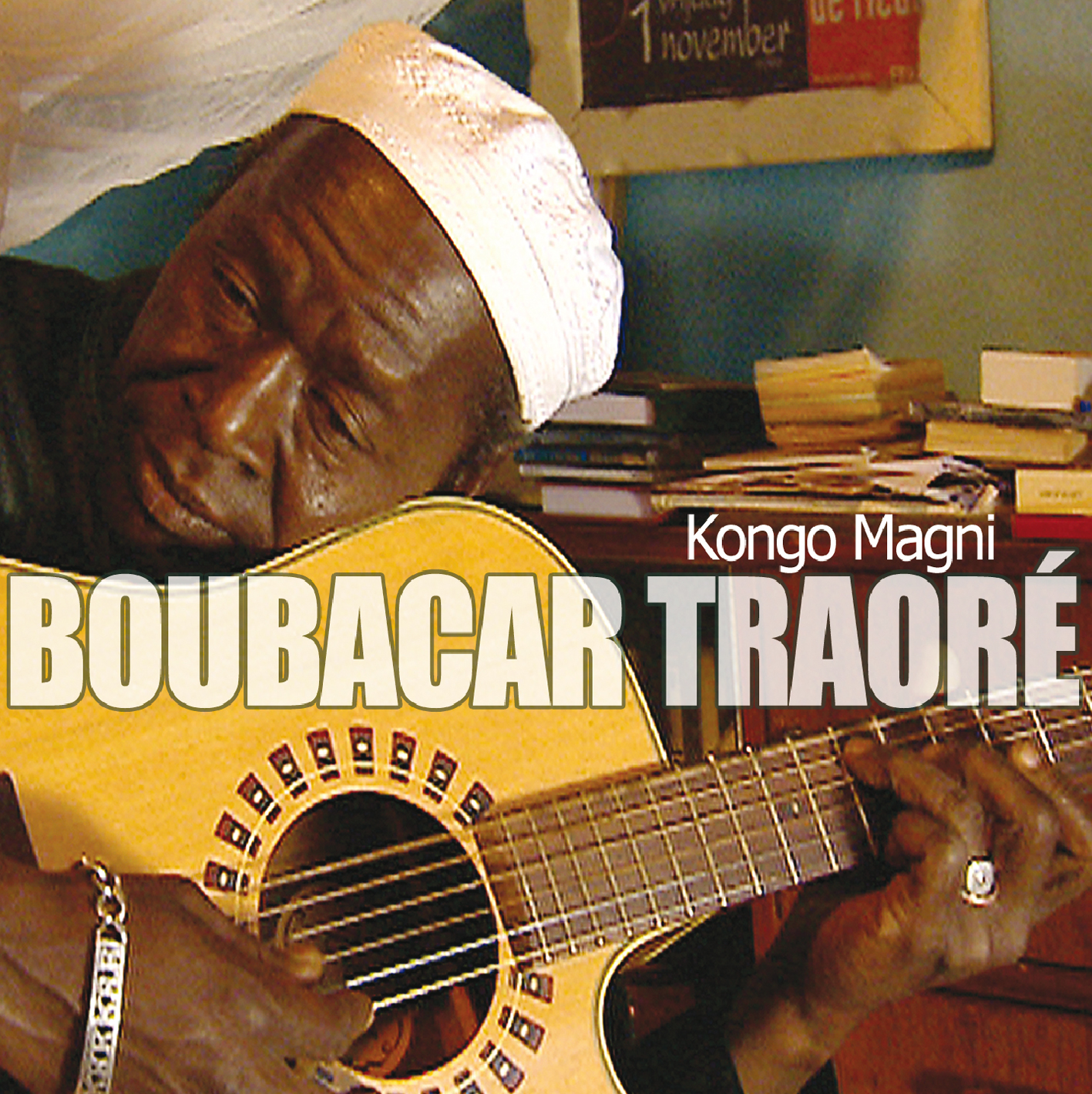

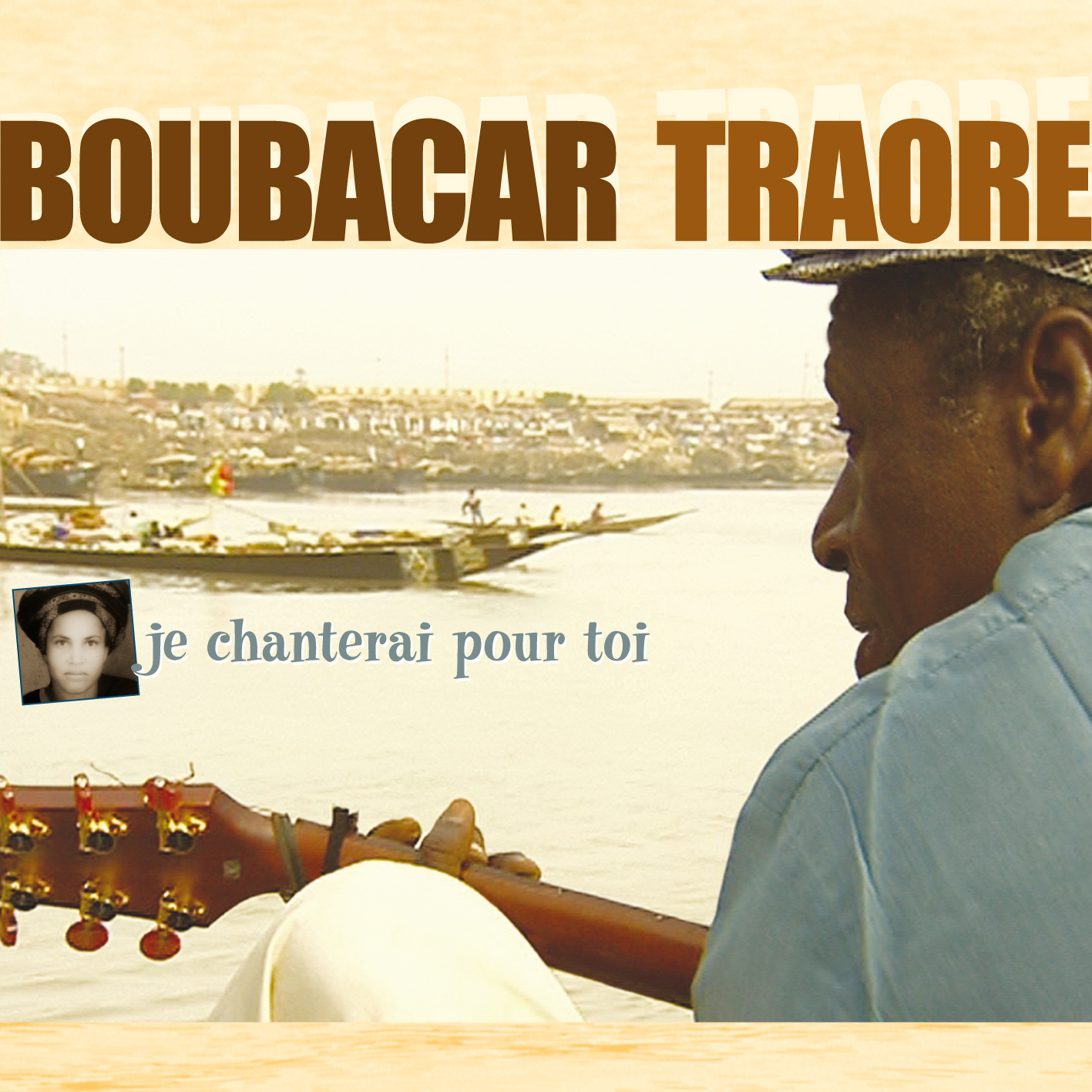

In Paris, an English producer discovered him and took him to the studio to record his first album, “Mariama”, in 1990. Poignant, spare and melancholic, Kar Kar’s music had changed since his youth in the 60s. Now it was more refined, the art of a mature man expressing his heartaches and joys in song, his unique vocal timbre shrouded in nostalgia and poetry. Boubacar Traoré’s life changed quickly after the record’s release. He recorded another 6 albums: “Sécheresse” (Drought) in 1992; “Les enfants de Pierrette” (Pierrette’s Children) in 1995, “Sa Golo” in 1996, “Maciré” in 1999, music from the eponymous film directed by Jacques Sarasin: “Je chanterai pour toi” (I’ll Sing for You) in 2002, and “Kongo Magni” in 2005. Kar Kar made up for lost time, triumphing on stage first in Europe and then in the United States and Canada.

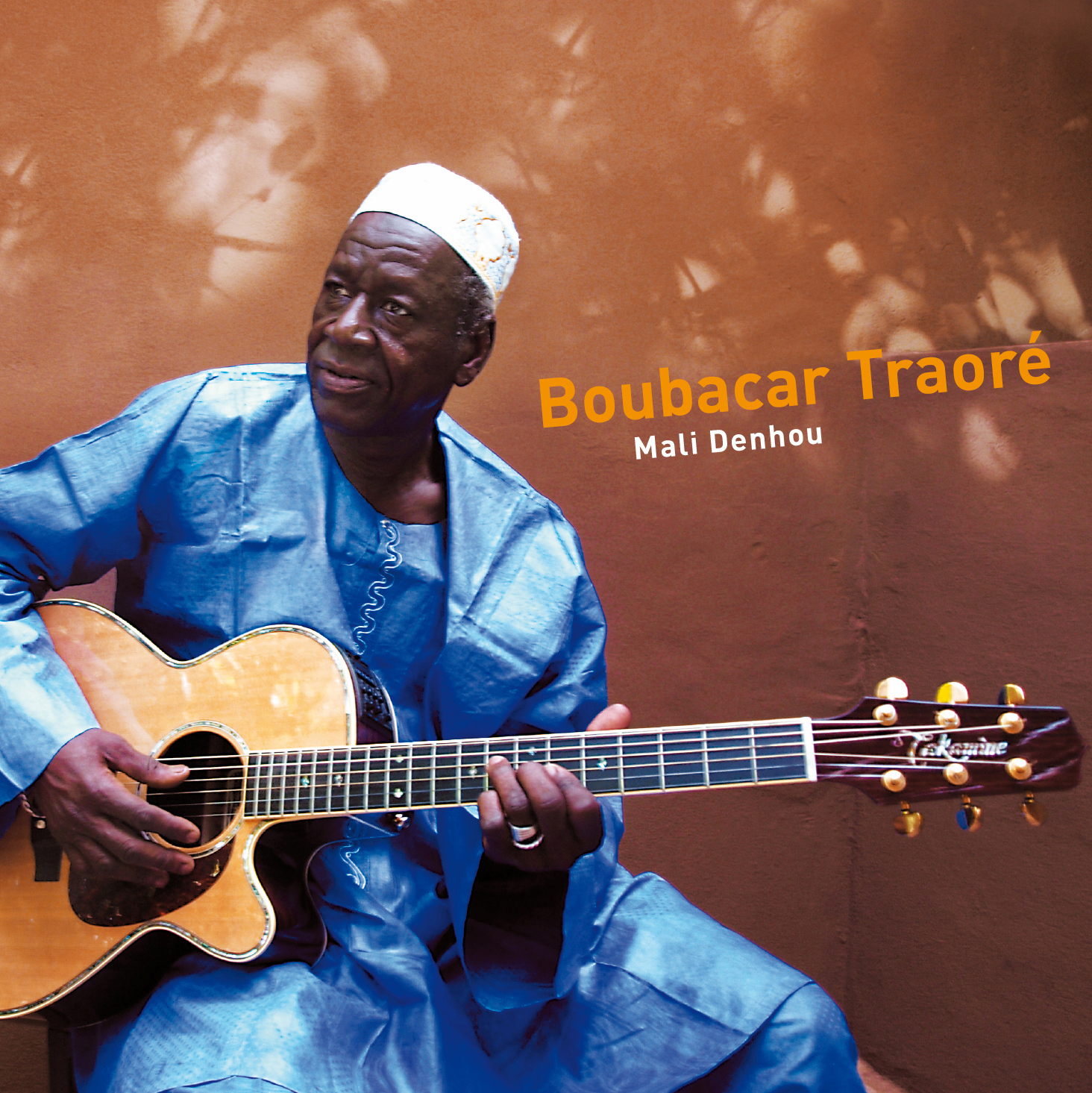

When Lusafrica bought the Marabi label in 2010, it is naturally that José da Silva proposed to Boubacar to join the catalog of Cesaria Evora and Bonga. Released in 2011, “Mali Denhou” is Kar Kar’s first album since 2005. It is recorded in June 2010 at Studio Moffou, on the outskirts of Bamako, with the same musical cast who had performed with him all over the world for years. The first takes were laid down with his old friend Madieye Niang on gourd and Vincent Bucher on harmonica, playing in live conditions.

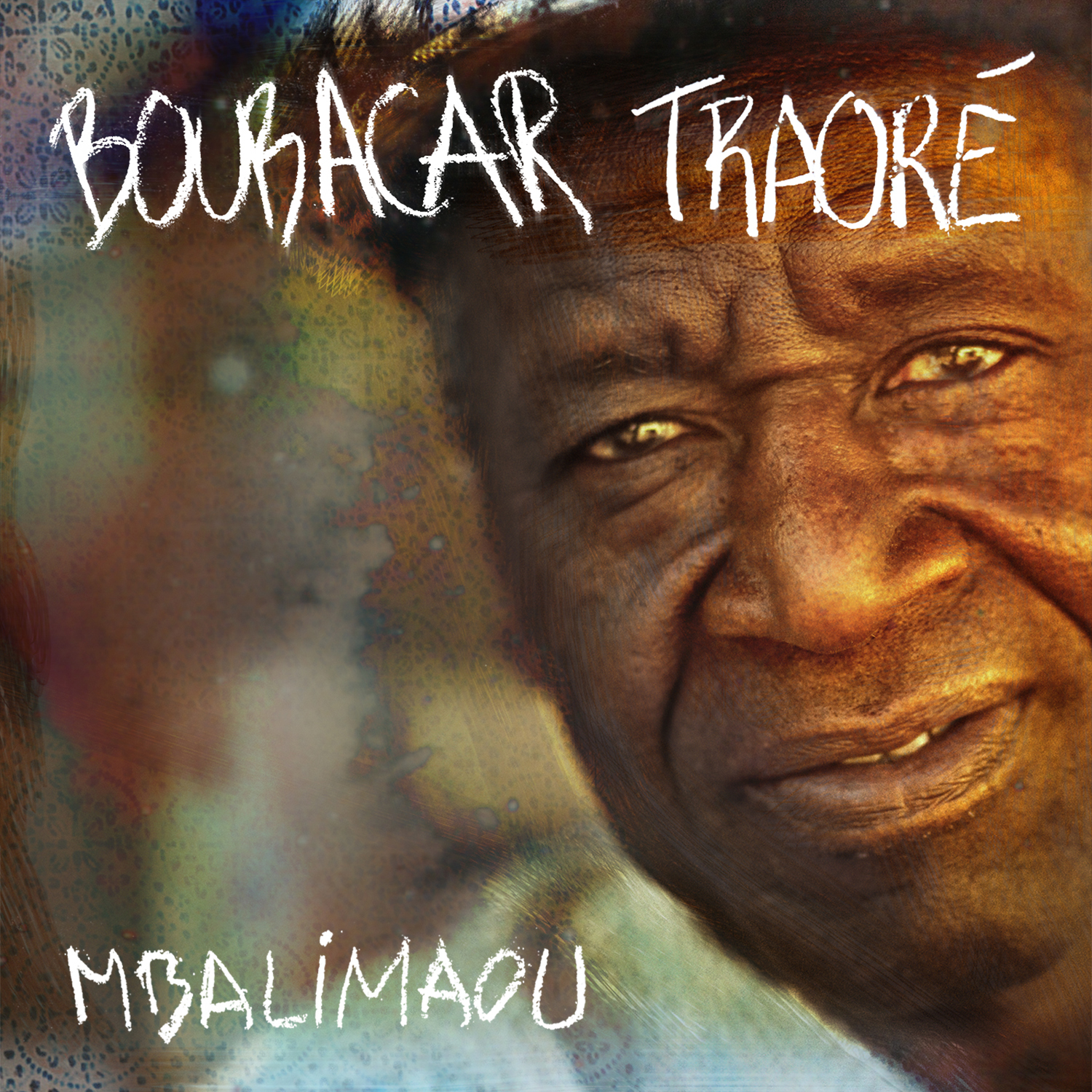

The following album “Mbalimaou” (2015) was recorded at the Bogolan studios in Bamako. As with each new recording, he has added new, different touches to his music, but without losing sight of the basics that make up his supremely distinctive style. Accompanied by discreet percussion – from the young Babah Koné, precise and steady on the gourd, Yacouba Sissoko on the karignan, shaker and small traditional percussion instruments, Vincent Bucher on the harmonica and Fabrice Thompson, a drummer and percussionist from Guiana, who seasons tracks that include “Hona”, “Mbalimaou”, “Kolo Tigi”, “Saya Temokoto” and “Africa” with a heady mix of spice and original beats, Boubacar weaves gloriously simple patterns of guitar and inimitable vocals into these new songs, written whenever he could spare a moment between laboring in the fields and touring internationally. Ballaké Sissoko, a musician he has worked with before, has always been a fan. He joined in the album’s artistic production and his playing fits easily and comfortably into the elder man’s music. Ballake’s generosity, open-mindedness and responsiveness did a lot to create a relaxed, positive atmosphere during the sessions. His subtle, elegant kora perfectly complements the guitarist’s fluid, minimalist approach.

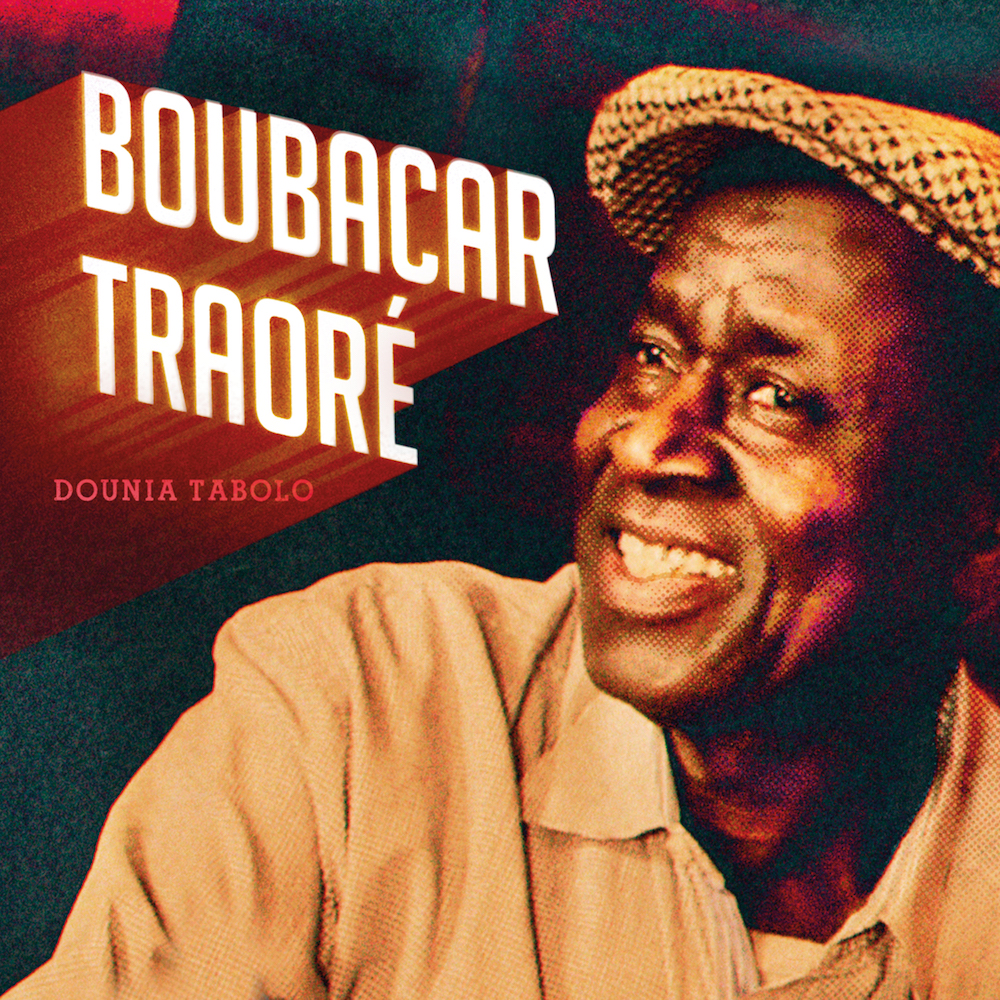

It is in the United States, in Lafayette Louisiana, that Boubacar Traoré wished to record his third album for the label Lusafrica. The guitarist’s intention was to change the coloration of his songs (old numbers like “Dounia Tabolo” ou “Kanou”, and new ones, “Ben de Kadi”, “Mousso”) while conserving their original character. So it is with musicians from the Southern States of the USA he had met on tour, Cedric Watson on violin and washboard, and Corey Harris on guitar, that he undertaked the recording of his album “Dounia Tabolo” at the end of 2016. And when he told them he wanted to add a cello and female voice to the album, Cedric Watson suggested Leyla McCalla. This recording is a new milestone in the work of this extraordinary but modest artist. From blues to folk and Cajun to Zydeco music, his new traveling companions have provided a touch of folly and swing (Cedric Watson), blues depth (Corey Harris) and discreet elegance (Leyla McCalla). More than ever, Boubacar Traoré has shown himself to be the living, vital connection between Mali and the Mississippi.

Boubacar Traoré is respected and acclaimed in his country, especially by young people. They are rediscovering the artist, one of the founding fathers and great ambassadors of modern Mandingo music. When his international tours end, Kar Kar returns to the piece of land he has bought on a hill in Bamako. There, he raises sheep and works a vegetable plot, his pride and joy. “In Mali, everyone is a farmer. It’s the most reliable way of making a living.”